Imagine for a second that the Roman Empire never fell. No Dark Ages, no Renaissance, just an uninterrupted stretch of togas, aqueducts, and bureaucratic tax collection. What would its economy look like today? Scholars estimate that at its peak (circa 200 CE so), Rome’s GDP was around $100 billion—pretty tiny by todays’ mega meal standards. It plodded along at an annual growth rate of maybe 0.1–0.2%, stretching to a whopping 0.5% in a banner year. But let’s be generous and apply that stellar 0.5% rate for the last 1,800 years. Fast forward to today, and Rome’s economy would sit at a tidy $900 trillion—roughly nine times today’s entire global GDP.

Sounds completely absurd, right? And yet, here we are in our financialized wonderland, where anything less than 2% growth gets politicians booted from office, Pension plans are designed around investment returns of around 6% annually, and retail investors actually tend to think 8–10% decent because, well, that’s just the way things have been for a while.

Our collective recency bias is so strong that hardly anyone questions whether these expectations are even remotely realistic on a planetary scale. Thinking beyond the next quarter is already a stretch—thinking one generation ahead is practically science fiction. And considering anything on the scale of humanity’s 300,000-year existence? Forget it. That kind of perspective definitely won’t get you a corner office.

I mean, it’s not like humans have never thought long-term before. The Haudenosaunee (Iroquois) Confederacy literally enshrined long-term thinking into their governance, ensuring that decisions would be made with an eye toward the next seven generations. Other Indigenous societies likely had, and many still have, equally long-term views on sustainability and economic decision-making—recognizing that the short term can’t Trump the long term.

But here we are, in a culture that stumbled upon fossil fuels, unlocking the cheat code for extracting Big Gulp amounts of energy, and decided that permanent refills were just the natural order of things.

Take GDP, the golden measure of economic success. It was proposed by Simon Kuznets in the 1930s as a handy way to assess policies meant to pull the U.S. out of the Great Depression. And while GDP has since become the economic deity we all bow to, Kuznets himself warned against using it as a measure of societal well-being. Why? Because it only captures measurable economic flows—ignoring things they are supposed to deliver like welfare, equity, and a reasonable relationship with our host planet.

Its a bit weird then that we treat GDP like a divine scoreboard, dictating how resources are allocated, how success is defined, and how economies are structured. It’s as if there were some mythical Kuznets fire hose, still gushing economic wisdom decades after the man himself warned us not to rely on it. And we’re all just desperately trying to drink from it, long after he shut the damn thing off.

But let’s be honest—you know this, I know this, we all know this. You see what’s happening, even if it feels like there’s little you can do about it.

So what does success look like as the world grapples with the MAGA-fueled fantasy that "you can have it all" forever? Let’s play out the math. If today’s $105 trillion global economy keeps chugging along at a 2% growth over the next 100 years we’re looking at an economy that would swell to $760 trillion—a >7x expansion.

Now, if we zoom out to a 1,000-year timeline—because, let’s face it, species-level thinking (aka actual sustainability) probably shouldn’t be based on the next fiscal quarter—our humble GDP would balloon to a mind-melting 40 sextillion. That’s a number so absurdly large that there is no point even trying to break it down. So yeah, things likely slow or even reverse eventually.

But maybe I’m missing some brilliant economic logic here. Let’s humor the infinite-growth crowd for a second and see what the energy cost of all this would be.

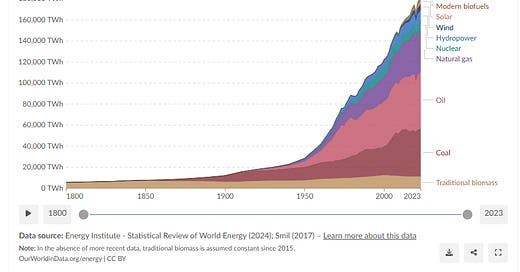

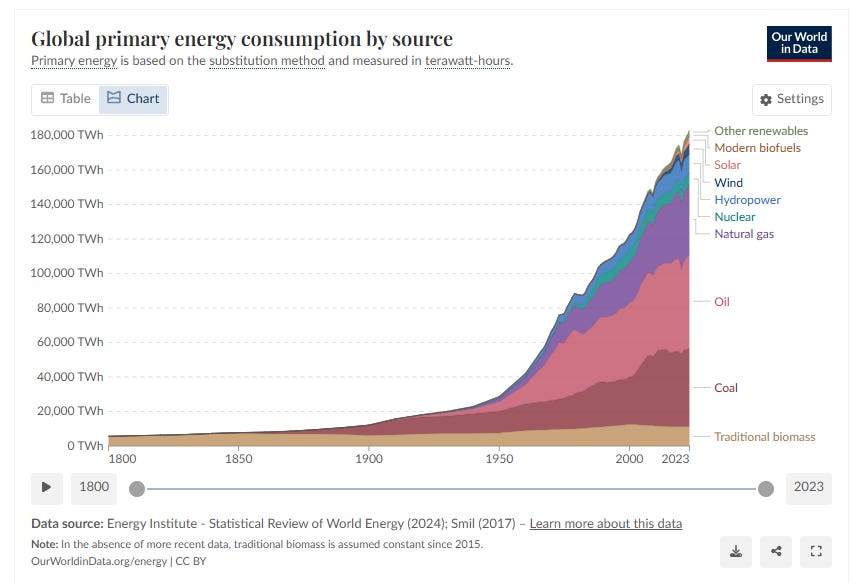

Right now, the global economy runs on about 18 terawatts of energy (fossil fuels, renewables, nuclear—the whole mix). And historically, energy consumption has grown at about 2.3% per year. Doesn’t sound like much but…

…factor in rising demand from AI and other tech, and some regions are actually projecting a significant increase in that growth rate. But let’s be reasonable and assume that eventually declining population growth keeps it to 2.0%, matching GDP.

Even then, by 2100 we’d be burning through 130 terawatts. Keep extrapolating, and in just 1,500 years or so, our energy needs would exceed what the sun puts out. And since Earth is smaller than the sun, it would be hotter here than there. So like, toasty1.

Clearly, this whole infinite-growth fantasy is, well, cray-cray. The Holy Roman Empire lasted about 500 years (not counting the eastern Byzantine version, which provided the 1000 year moniker)—not because it figured out how to compound growth indefinitely but precisely because it didn’t. Sorry, Adolf, but history doesn’t actually reward empires that try to expand forever.

In fact, nothing in nature grows infinitely. No ecosystem, no species, no empire. Even the largest trees on the planet, before we cut them down, with widths of 5-6m and heights of 70-80m, eventually reached biological limits. And as much as we like to pretend otherwise, humans are still just another animal living inside a planetary petri dish with very real, if somewhat malleable, boundaries.

No doubt, some of you are probably thinking, “Yeah, but what about efficiencies? Technology has made incredible strides in boosting efficiencies, which has powered decades of robust economic growth!” And you're right—technology has made remarkable improvements. However, let’s not get too carried away, because the low-hanging fruit has already been picked. Efficiency gains from combustion and electrical conversions have already been jacked by 70–80% over the last 50 years. Now, we're reaching a point where further improvements are getting harder and harder to come by.

Let’s take a couple of examples to highlight how things are likely to change in the coming years.

Heat pumps are a fantastic step forward in making HVAC systems more efficient. But like all good things, there are limits. For example, if average outdoor temperatures rise by just 1% in the summer, a heat pump’s efficiency could drop by 5-7%, depending on the setup. That’s because, to keep your house at a comfortable 22°C while the outdoors bake at over 30°C, your heat pump is ejecting air at more than 40°C. Now, imagine that on a massive scale, with a city of heat pumps running at full tilt. Not only does it raise the local temperature even further, but that efficiency boost starts to look less and less like a “free lunch.”

Then we get to the rise of AI, which is only going to ramp up power demand. Much of that demand is going to rely on nuclear and natural gas plants, which come with massive cooling requirements. Water cooling is typically the most efficient (over air), but no matter how you slice it, the heat has to go somewhere. As global temperatures rise, cooling these plants is going to become more difficult, and local water or air temperatures will inevitably climb as a result.

And if that’s not enough, the reduction in glacial melt—which used to provide nice, chilled water for cooling purposes—only adds another layer to the problem. As glaciers retreat, we’re left with even less and warmer water to help keep things cool. So, the more energy we demand, the worse the compounding issues get. It’s a classic case of the increasing complexity that our brains just don’t seem yet to cope with well (more of this latter). Our massive system ramp in just 200 years requires rewiring that takes millenium in an evolutionary context.

Most of this is pretty basic stuff—things that are often covered in high school science or environmental studies—and yet, somehow, market logic insists on turning a blind eye to all of it. Why is that? Well, the truth is, finance professionals today, even of the ‘sustainable’ ilk, are still hopelessly smitten by the allure of perpetual, steady-state growth. In fact, projecting this is what got us to the adult table in the first place. We’ve become so enamored and remunerated on the idea of unlimited returns that we’d rather submit the ‘keep digging’ business plan than be the canary in the coal mine.

Whether you're at a pension fund, a private equity firm, or a fund company, the rules are crystal clear: Deliver returns that beat the benchmark. That's the fiduciary gig and its what you signed up for. Doesn’t matter if that benchmark is based on the Billionaire Bros Club (BBC) vision of the future (cryogenics? colonies on Mars? tech islands?) That's your job, no questions asked. And guess what? That’s also pretty much the job of the government these days too: beat your neighbours. The heavy lifting—the real, inconvenient work of understanding limits—gets left to zealots, anarchists, and, of course, your kids.

Thankfully, at least they are actually grappling with the big issues in school—climate change, earth boundaries, restoration, all that stuff we’re not supposed to talk about - but that are still on curriculum - for now. This happens, of course, before they graduate to those Ivy League business programs, where they form a conga line to funnel from a recharged Kuznets’ GDP hose, now freshly fueled by the BBC fountain of “endless growth” and “technological betterment.”

So, the real question is—when does growth slow down enough that it becomes impossible to ignore? Now? 100 years? 1,000? Do natural boundaries break first or does the financial system thats built on servicing debt? Regardless, once the delusion is gone the good news is that our focus will inevitably pivot to human wellfare and restoration.

So even if you’re the ‘Debbie Downer’ in the boardroom today (which, let's face it, you probably are), embrace it 😉 - you’re just asking questions that we’ll all have to reckon with sooner or later.