Sustainability without a focus on the long-term is about as useful as a chocolate teapot. But in the wacky world of fiduciary finance, "long term" typically means something like retirement planning or pension liabilities. As I’ve said before, what's glaringly absent is any genuine long-term perspective on humanity’s place on this planet. Not that it's a huge surprise—why would finance folks bother with anything beyond their investment horizon? Yet here we are, with trillions poured into the Principles for Responsible Investment, and corporations falling over themselves to make net-zero pledges and adopt nature-based strategies. These are the hot potatoes politicians would increasingly rather not touch, so it's really up to investors to take in as much of the big picture as possible. And really, what better timing? If COVID didn’t turn you into a science geek with some humility, I’m not sure what will…

Reading up on the latest in human origins during that pandemic induced time out, I expected to find that science had reinforced our species' long list of advantages that catapulted us to the top of the food chain. I mean, that would justify us arrogantly dubbing our epoch the Anthropocene, right? We were destined for greatness, after all!

Yeah, no. Not really. It turns out that the evidence increasingly suggests our most obvious traits were neither exceptional nor rare in the grand evolutionary circus. So, what’s the deal?

Let's kick things off by dismantling two of the cornerstone myths of the 'we're amazing' narrative to see where things went sideways: bipedalism and tool use. If you remember anything from your prehistory lessons, it’s probably these two so-called evolutionary superpowers. In later notes, I’ll take a swing at other favorites like our ‘quest for fire,’ ‘gift of the gab,’ and ‘fashion sense.’ Spoiler alert: our superiority complex might be in for a reality check.

Pumped up Kicks

In the grand, somewhat bizarre saga of human evolution, nothing quite tickles the imagination like our ancestors leaving their footprints in the sand. Or volcanic ash, to be exact. The most famous of these footprints, discovered in Laetoli, Tanzania, by Mary Leakey in 1976, are like a drunken text from our past: "Hey, look at us, we’re walking while touching our noses!”

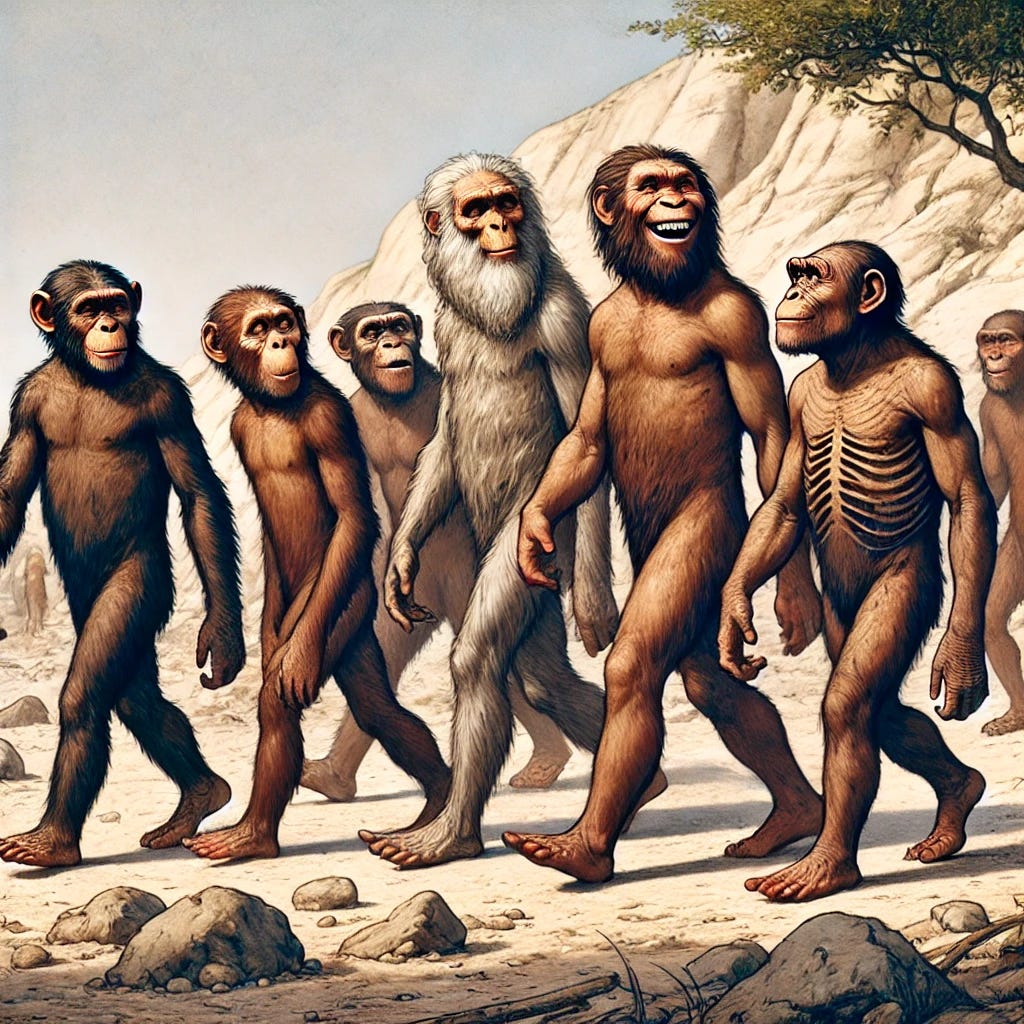

These ancient strolls, dated to a mind-boggling 3.6 million years ago, threw a spanner in the works of our understanding of evolution. The narrative decades ago used to be simple: walking on two legs = human. So think maybe 300,000 years ago. But here were these footprints, cheekily predating what we thought was our debut on the two-legged scene. The easiest solution? Sluff them off as bear footprints (yes, this actually happened!) . Bears walk on two legs sometimes, right? Crisis averted. Let’s keep that evolutionary chart showing a neat, orderly march from ape to modern human intact.

But Leakey really wanted to associate the prints with the life of the paleo party, ‘Lucy’, discovered a couple of years earlier in 1974 and named after a Beatles song. Because, hey, science can be fun too! She was named Australopithecus afarensis, a species that could casually stroll on two legs. With Lucy and the Laetoli footprints now linked, it would be clear: walking upright wasn’t our big entrance as Homo sapiens. Cousins that were far more ape-like than human had crashed the bipedal party way earlier.

In 1978, more footprints were found - 70 of them! It was like discovering the membership list to a prehistoric neighbourhood walking club. This confirmed that Lucy and her gang weren’t just one-off bipedal enthusiasts; walking on two legs was their thing.

But the plot thickens. In 2019, a reexamination suggested some might belong to another species. Imagine, multiple hominids (species in our family tree), strutting around, all thinking they’re the next big thing in evolution. It's like Mother nature threw a bunch of options on the wall to see what would stick. The ‘born to run’ thesis is fun (although the barefoot craze it spawned was a tad painful). It's just that it turns out there were a bunch of other hominid species who also seemed to have run - but out of luck. So it was hardly a basis for exceptionalism.

The lesson here? As told repeatedly in the archaeological record, our journey from ancient footprints to modern civilization isn’t a straight line. It’s more like a dance, with different species cutting in, each with their own moves, until only one – us – remains on the dance floor. But as we know, being the last one dancing doesn’t always mean you’re the best; sometimes it just means you’re the only one left.

Copycats

Commentators today are in a curious habit of sketching our technological timeline as though nothing much happened until, say, the Renaissance, with an occasional nod to the Egyptians and Romans for good measure. Before that? Prehistory gets the ‘stone tool’ and ‘bow and arrow’ stickers, and we move on. It’s as if our ancestors were merely doodling in the margins of history’s notebook (typical is Table 1, where the spiral covers most of our apparently boring and unproductive existence).

But here’s the thing: Those stone toolkits are more than just relics; they’re the ancient equivalent of Silicon Valley startups. Archaeologists unearthing these gems aren’t just digging up old rocks; they’re uncovering the iPads of the Paleolithic era. Forget digital neural networks, these tools were the result of actual neural networks spanning generations, echoing a cultural R&D process that facilitated a synergistic existence with other living things.

Today, no one likes a copycat, right? It seems even accidentally humming someone else’s tune might land you in court. But if our ancestors had been such sticklers for originality, we’d probably still be living in that world of, well, sticks and stones. Apparently prehistory was less about copyright and more about, “Hey, that looks neat; let me try it!” Imitation led to accidental improvements and, before you knew it, innovation! Go figure that today we need think tanks and government funding to facilitate something we did naturally for most of our existence.

“At some point in the Homo lineage, individuals began to acquire the ability to copy others’ actions without the need for specific training or rewards…. Whatever this ability is, it set us on a path to acquiring technologies, and we have moved from a slow to a breathtaking pace of technological development’. Mark Pagel as quoted in Humans1

The key here is ‘in our lineage’ - so not specific just to us modern humans (sapiens). Bipedal Lucy already packed a bit of a punch using rudimentary tools that have been dated at sites as old as 3.3 million years ago, also in Kenya. Other species at the time were also getting in the charcuterie game, with recent discoveries of butchered animal bones from Kenya dating to 3.4 mya but attributed to one of Lucy’s cousins, Kenyaanthropus (don’t even ask).

Some 2.6 million years ago, our hominid forebears were wandering around, and one of them picked up a rock. Not to throw at a rival or bash someone’s head in – but to make another rock sharper. Welcome to the Oldowan tool industry, named after the Olduvai Gorge in Tanzania, where archaeologists first stumbled upon these ancient "gadgets." They’re basic – imagine the first version of any tech product – but hey, everyone has to start somewhere.

Fast forward to about 1.76 million years ago, and our ancestors are getting crafty. Enter the Acheulean handaxe, the Swiss Army knife of the Stone Age. These tools are sleeker, sharper, and multi-purpose – found everywhere from the warm plains of Olorgesailie in Kenya to the less balmy locales of Boxgrove in England. It’s like our ancient cousins are saying, “Look, we’ve figured out symmetry!” It’s a big leap from smashing rocks together.

Then comes the Middle Stone Age party, around 300,000 years ago, when our species, H. sapiens, was now mingling with Neanderthals and other undesirables. Happily, things were getting fancier. Sites like Blombos Cave and Sibudu in South Africa have spat out evidence of tools that aren’t just about survival. They’re about style, baby. We’re talking blades, points, and even early attempts at art. It’s like our ancestors are not just surviving; they’re thriving with a bit of flair.

By the time we occupied another South African site called Pinnacle Point around 170,000 years ago, we were adapting to climate change like pros, years before it became a global summit agenda. Our diet? A culinary masterclass in ancient 'surf and turf,’ with a side of carb-rich geophytes. We were crafting microblades and spear tips like the original Apple geniuses, boosting our brainpower with an omega-rich diet.

Fast forward to our so-called modern era (some 40,000 years ago), where we’ve traded microblades for microchips. We pride ourselves on our engines and AI, yet ironically, our brains have been quietly following a minimalist trend, having even shrunk a bit from 20,000 years ago. Neanderthals, poor suckers, actually had larger brains, so size clearly isn’t everything.

We've only been dabbling in this whole agriculture thing for about 12,000 years, which leaves a cool 280,000 years when we were fully human but perfectly content with gathering and hunting. The folks hanging out at Pinnacle Point for over 130,000 years may not have had Netflix, but they also didn’t need Ozempic or a Peloton to get by.

Our obsession with technological progress—with its laser focus on the latest gadgets and life-extending pharmaceuticals—completely misses the bigger picture. Longer lives mean nothing without cultural longevity. Just ask the Romans or the Aztecs. It's like getting excited about the newest smartphone while ignoring its terrible battery life. Those civilizations were veritable technological skunkworks, yet they disappeared in relatively short order. Contrast this with those early toolkits that served their purpose for thousands of millennia - contributing to underemphasized things like our survival and continued evolution.

Yet with other hominid species walking around with their own versions of the Swiss Army knife nothing has answered the question of why us? We’ll continue to dig into that a bit more in future notes...

Humans, Perspectives on Our Evolution from World Experts, Sergio Almecija. Columbia University Press, 2023.